While dopamine is often known as the pleasure chemical, it would be better termed the anticipation chemical. It is triggered in looking ahead to a possible reward. It is enhanced in the face of novelty and uncertainty — when you envision something good happening, but aren’t entirely sure that it will, or exactly what it will be like.

Dopamine is a neutral neurotransmitter, itself neither good nor ill. But it can be handled and harnessed in ways that either facilitate, or hinder, your ability to lead a flourishing life.

In the hindrance category, two main issues arise.

We talked about the first last month: you can get hooked on the giddy, exciting surge of motivation dopamine lends to the initial stages of pursuing something . . . but find that you can’t stick with that something after this early wave of energy fades. This is particularly problematic in the context of longer-term commitments: while the dopamine-driven honeymoon period only lasts a short time, a relationship, goal, hobby, or faith can require years, even decades of effort. People who can’t transition from the dopaminergic excitement of wanting something, to the distinct satisfactions of actually having it, end up abandoning one half-finished project after another, endlessly chasing after the next dopaminergic high.

Yet while we can become too much dependent on dopamine, many people suffer from a different issue: having too little dopaminergic excitement in their lives.

Dopamine is a pleasure chemical, in that anticipation produces pleasure. And learning to structure your life in a way that maximizes this particular pleasure is a real art.

The Problem of Dopamine in Adulthood

Do you remember where we began the previous article about dopamine? It was with a quote from Casino Royale, in which Ian Fleming described the way James Bond bemoaned the “conventional parabola” of his relationships: they started out with upwardly arcing attraction, but, once consummated, quickly devolved into boredom and miserable break-ups.

Interestingly, that aside was in fact used to juxtapose these inferior past relationships with the one Bond builds in that book. Convalescing after a secret operation gone awry, 007 is physically incapable of having sex with his love interest, Vesper, and is forced to postpone the consummation of their relationship until after he recuperates. So, instead of jumping right into bed with her as he does with most women, he gets to know her slowly, letting their relationship, and the sexual tension between them, gradually build:

In the dull room and the boredom of his treatment her presence was each day an oasis of pleasure, something to look forward to. In their talk there was nothing but companionship with a distant undertone of passion. In the background there was the unspoken zest of the promise which, in due course and in their own time, would be met.

When the pair finally do consummate their relationship, their lovemaking is electric and Bond is so smitten with Vesper that the typically roguish secret agent decides he’ll propose marriage.

Such is the power of anticipation.

Anticipation is pleasurable tension. Charged expectancy. It is a feeling encapsulated in the desire one feels at the sight of a gift-wrapped box to know what’s in it. Dopamine senses a possible reward, paints a rosy picture of what it might be at its most ideal, and produces the desire to get at it, to experience it firsthand, to find out just how good it might be.

Once we know what’s in the “box,” dopamine dissipates.

Thus, while we typically think that what we most want is to get what we, well, want, the most intense current of pleasure actually lies in looking forward to getting what we want. Everyone knows that the anticipation of Christmas is far better than Christmas itself. Similarly, research shows that people enjoy the anticipation of their vacations more than the vacations themselves. In the throes of expectancy, a sense of impending magic builds; we get to contemplate the still-perfect picture of what lies ahead, untainted by the nuanced messiness of reality.

Given that the exciting charge given off by dopamine-driven anticipation surges in the face of newness, novelty, firsts, it’s unsurprisingly in short supply in many a routine-hardened adulthood that includes everything but.

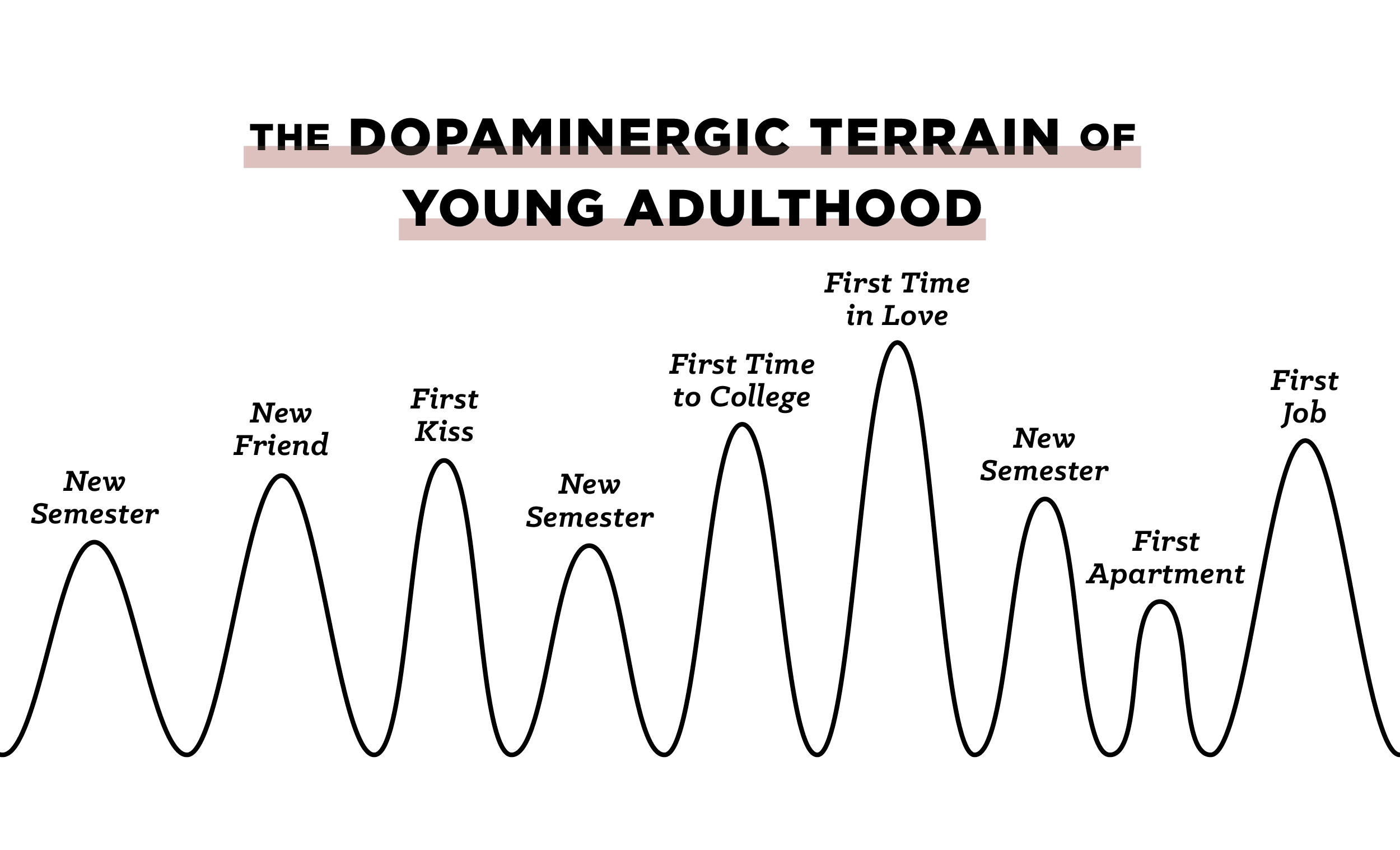

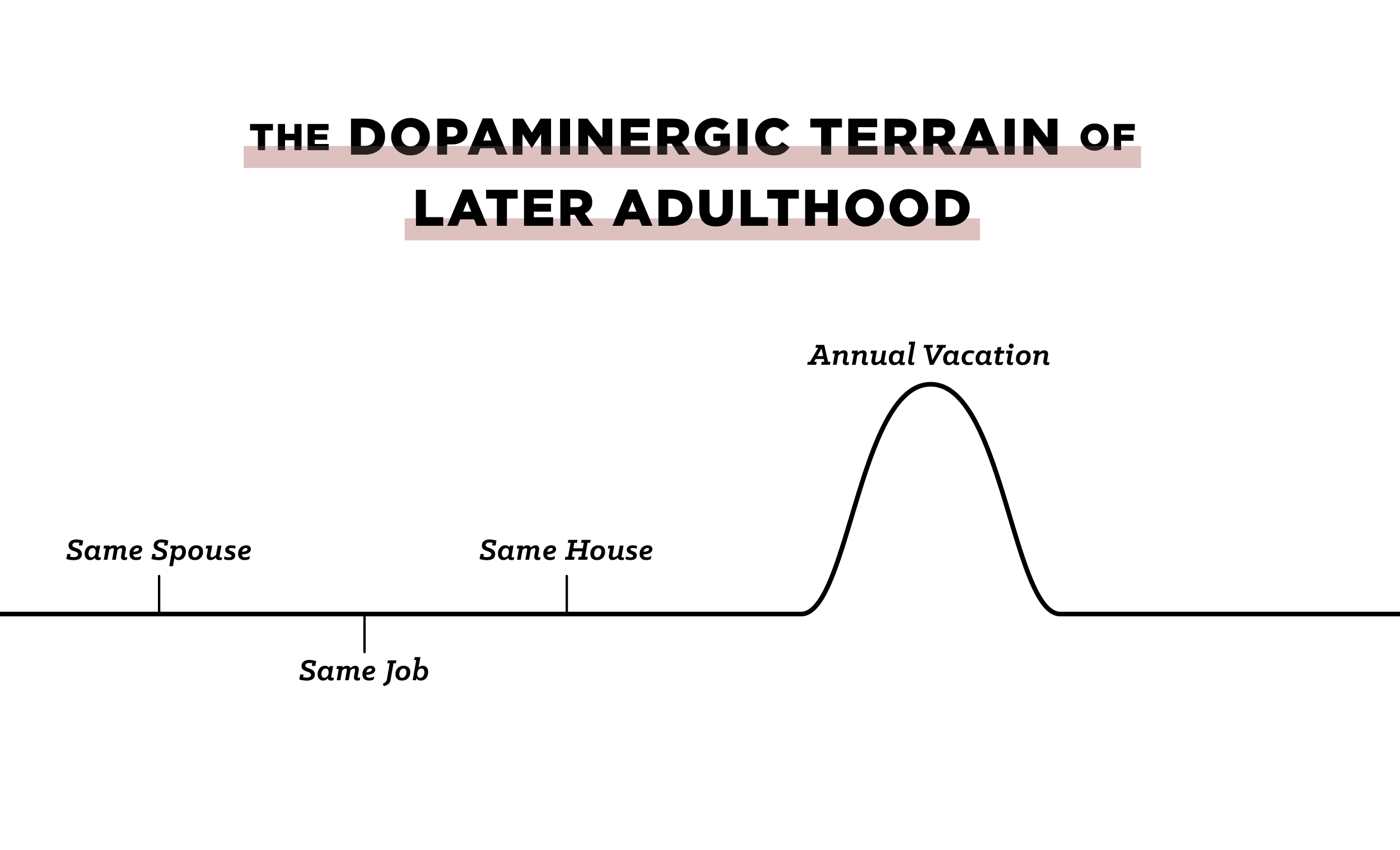

Consider the charts of the dopaminergic “terrain” of young adulthood versus later adulthood:

Young adulthood is stacked with the arcs of dopaminergic excitement; later adulthood shows a life flat-lined. One is aesthetically interesting; the other is monotonously uniform. One evokes the thrilling landscape of a rugged mountain range; the other, the sterility of a desert.

Of course, the downward facing slopes of youth’s undulations do lend life more anxiety and insecurity, and transitioning to greater stability in certain areas — especially those longer-term projects mentioned above — is a healthy and desirable part of maturation; rather than constantly trading in life’s foundational building blocks for brand new go-rounds, most people do want to settle down with someone, stick with, if not the very same job, the same vocational path, and live in a single place long enough to put down at least a bit of root-age.

But, while you don’t want to restlessly ride the parabola of the dopamine cycle in areas in which you’re looking to create things that last, there’s plenty of room in life to incorporate “one-off” experiences too. As well to maintain a little novelty — and the dopaminergic excitement that accompanies it — even within the more stable structures of your adulthood.

Cultivating the Art of Anticipation

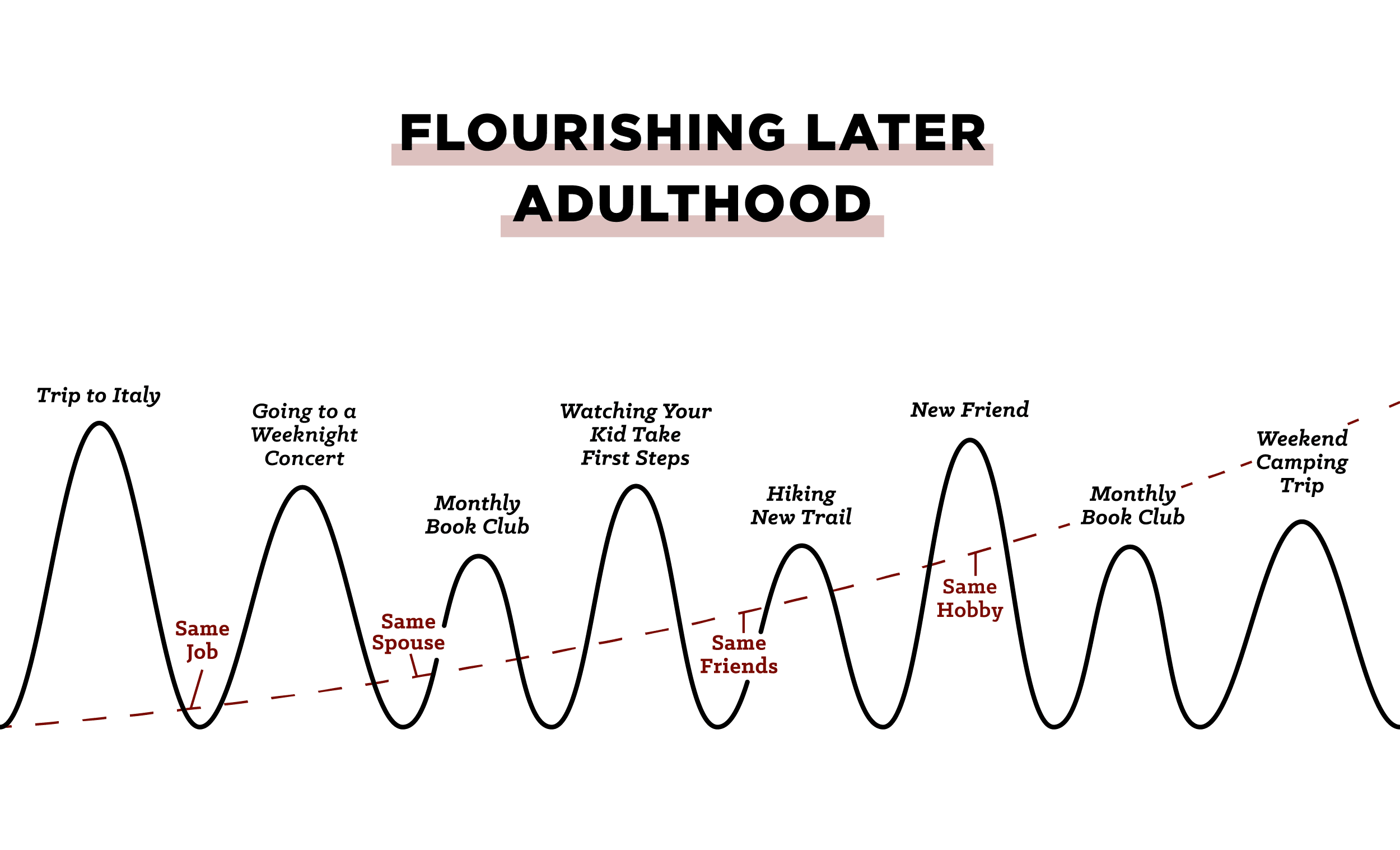

A flourishing adulthood comprises a mixture of the familiar and the novel. Satisfaction is found in not only keeping life’s foundational building blocks (spouse, friends, home, job) stable, but in their progressive improvement. At the same time, new experiences and firsts are sought; while the intensity of the dopaminergic undulations of young adulthood cannot be wholly replicated, with intentionality, later adulthood can still have a varied, interesting landscape.

To experience more of the dopaminergic charge of anticipation in life, one must cultivate the following two factors:

Do Novel Things (In the Form of Newness or Uncertainty) . . .

Dopamine is set off when we approach something novel.

While such novelty may often be scarce in adulthood, it doesn’t have to be. There are always new friends to be made, new books to be read, new hobbies to try, new trails to hike.

While we may cross off many of our major firsts in our younger years, there are ever more firsts to be notched throughout the decades to come: first time visiting X place, first piano recital (taking up a musical instrument needn’t only be for kids), first marathon. It doesn’t have to be big stuff, either; your first time visiting a new restaurant or attending an art festival or museum will give you a tickle of excitement too. Plus, there’s all the firsts you’ll experience in witnessing your children experiencing their own firsts.

The novelty in your life doesn’t have to be strictly novel, either. Think of novelty not as limited to newness, but as anything that contains a degree of uncertainty.

Dopamine exists in any pocket of space and time in which you don’t know exactly what to expect.

This can occur when you’re going to do something you have done before, but haven’t done for awhile.

When you contemplate an evening eating a frozen pizza and watching Netflix, you know exactly what to expect, so there’s no dopamine, and no “buzz” leading up to it.

But when you do something you haven’t done in awhile, and which includes variables that aren’t 100% certain and can change, your brain kind of “forgets” exactly what it will be like and senses at least the possibility of the unexpected. There’s room for error in the gap between how rewarding you remember something being last time, and how rewarding it might be this time, and in that gap, dopamine can emerge.

The presence of other people is a variable that always ensures a level of uncertainty, and thus dopaminergic anticipation. You never know exactly how a human interaction will go, particularly with folks you see less frequently, rather than, say, live with day to day. Will your chemistry ignite? Will you impress with a great joke or insight? Will you awkwardly bomb? Will you argue? Will some new layer of the other person, or yourself, be revealed?

Thus, if you want more dopaminergic buzz in your life, it behooves you to socialize more often.

. . . Scheduled for the Future

Your smartphone is a never-ending gobstopper of dopamine. Because of its perfect slot-machine-like set-up of salient but uncertain rewards — Will I have a new text? How many likes has my Instagram post gotten? — the dopamine-driven itch to check one’s phone feels nearly irresistible. That irresistibility, however, is also one part of why phone-produced dopamine doesn’t give us any real pleasure; as soon as the anticipation of a possible digital reward crosses our minds, we kill it in the crib by glancing at our screens. (The other part, is that unlike dopaminergic motivation that can lead to deepening relationships, sharpening skills, and participating in new experiences, the dopaminergic urge to check your phone doesn’t terminate in anything beyond the intake of ethereal “one-byte” indicators of superficial status.)

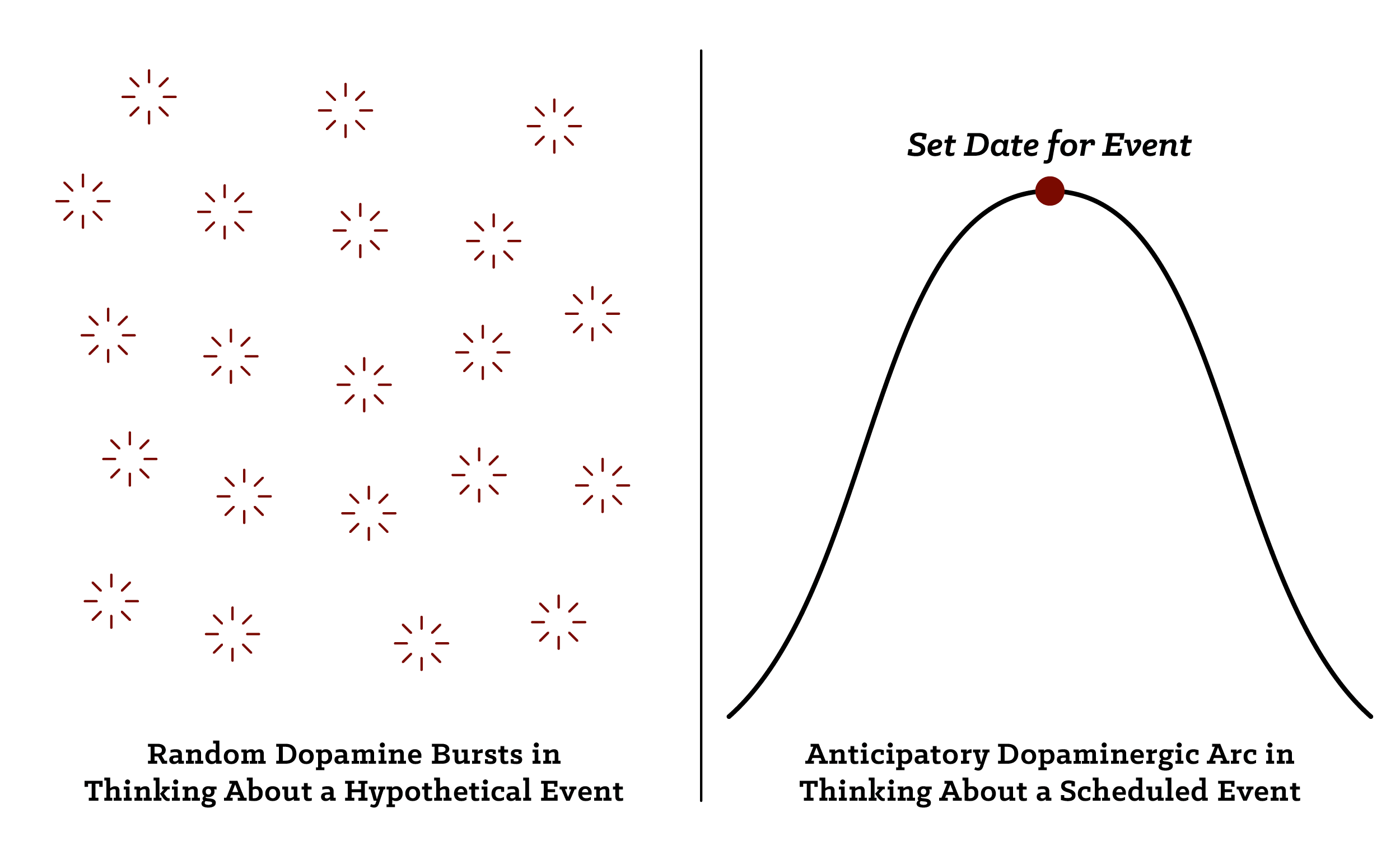

If you decide to do something novel, and immediately act on that impulse, there is little room for anticipation — and its attendant charge of dopaminergic excitement — to build.

The key to cultivating the art of anticipation is thus not just to do new things, but to wait to do them.

While you can release dopamine in little random bursts by hazily contemplating a possibility for which you’ve made no real commitment, the real magic of anticipation happens when you schedule an event, that includes an element of novelty/uncertainty, for a specific future date.

When you delay the gratification of your desire, and can look forward to a concrete time at which it will be fulfilled, you allow the delicious pleasure of anticipation to slowly crescendo as it draws closer. This pleasure is not negated, and can in fact be enhanced, by a feeling that frequently runs in tandem with anticipation: stress. A little stress (and even fear) will often accompany the effortful means that lead up to an enjoyable end — whether a trip you’ve planned for yourself or a party you’ve planned for others. But it can be a healthy element in the charge surrounding dopamine’s upward arc; it is well we use the phrase “pregnant with possibilities,” for when there’s a “due date” for any upcoming event, the weight of expectancy grows heavier as that date approaches, until we’re finally ready to experience the elated release of that pent up, even uncomfortable tension.

There is therefore much wisdom in intentionally scheduling out your leisure time.

Finalize your vacation plans a year ahead, and you give yourself 12 months of anticipatory pleasure, anticipation that can be heightened even further if you lend more of your thoughts to the trip to come — reading up on the destination, refining your itinerary. Or plan a few smaller trips rather than one big one, to add more anticipatory undulations to the landscape of your life.

Deliberately plan your more “micro” recreation too: Plot out a hike or dinner date for the weekend — giving yourself something to look forward to as you make your way through the Monday to Friday grind. Arrange a lunch, a few days previous, to a novel establishment, with a rarely seen friend. Hatch a practicality-be-damned weeknight adventure.

Remember that the events you anticipate do not have to be novel in your having never experienced them before, but simply in having a degree of uncertainty arising from the time that’s passed since you did them last, and/or the presence of other people. One can in fact enhance the dopaminergic excitement surrounding such affairs by making them “seasonal”: standing dates, traditions, that happen every year, every month, even every week. Wonderful is the anticipation that rides upon a rhythmic current, the experiences that rise both familiar and new with each turn of the chronological wheel.

When you master the art of anticipation, you maximize the pleasures of looking ahead. Such expectancy doesn’t mean abandoning a mindful embrace of the present moment; rather, it lends a buoyancy which makes the weight of the present moment easier to bear.

0 Comments