With most women [James Bond’s] manner was a mixture of taciturnity and passion. . . . He found something grisly in the inevitability of the pattern of each affair. The conventional parabola—sentiment, the touch of the hand, the kiss, the passionate kiss, the feel of the body, the climax in the bed, then more bed, then less bed, then the boredom, the tears, and the final bitterness—was to him shameful and hypocritical. Even more he shunned the mise-en-scène for each of these acts in the play—the meeting at a party, the restaurant, the taxi, his flat, her flat, then the weekend by the sea, then the flats again, then the furtive alibis, and the final angry farewell on some doorstep in the rain. –Casino Royale

In the above quote, Ian Fleming describes the depressing cycle of Bond’s relationships with women.

But he is also describing the dopamine cycle that occurs not only with romantic passion, but in all areas of life.

Dopamine is often known as the pleasure chemical, but it might better be understood as the anticipation chemical.

This neurotransmitter is triggered by looking ahead, by imagining things that you don’t yet have in the present but want to secure in the future. Dopamine paints an idealized picture of what obtaining those rewards will be like, and how they will improve your life, which drives you towards them. It’s amplified by encounters with novelty, and the process of discovering and learning new things about something/someone. The uncertain and the unknown send it surging: Does she like me? What will I find in this place? Will I have a new text or email when I open my phone? Dopamine wants to find out.

When you’re beginning a new romantic or even platonic relationship, and have high expectations that this is the person you’ve been waiting to meet, who will fulfill your longstanding hopes, and you envision years of good times ahead with them, dopamine is fueling your excited, even giddy, optimism. When you obsessively check your phone for texts from said person, and can’t help — despite wanting to seem more cool and aloof — responding immediately and enthusiastically (“Sure!” “Can’t wait!”), dopamine is in the driver’s seat. It’s the same thing when you’re anticipating a vacation, and imagine how amazing the trip is going to be, or when you start a new job and feel all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed about it.

Dopamine is also triggered when we scheme and dream, plot and plan, and actively strive to get that which we desire — and it lends energy, elation, enthusiasm, and excitement that push us towards those goals. It makes you think about the thing/person you want all the time. It gives you single-minded focus — passion, longing, even obsession. Dopamine motivates you to make sacrifices that you wouldn’t in its absence; it makes things that would normally seem burdensome, feel easy.

If you typically hate waking up early, but happily accept an invitation to lift weights at 6 a.m. from a new friend you’re hoping to get to know better, dopamine is what helped you get out of bed. If you normally hate helping people move, but gladly volunteer to assist a girl you’ve got a crush on, dopamine is what motivated you to show up.

You feel the hope-inducing, motivational power of dopamine whenever you sign up for a new online program or download a planning app, and feel that “This, this is going to be the thing that finally turns my life around.” You feel it when you stay up late to work on a project you care about, and can barely bring yourself to break off to go to the bathroom. You feel it when you’re contemplating some big purchase you think is going to add a lot of happiness to your life.

In short, dopamine heightens your desire and expectations for possibilities/rewards you’re envisioning, motivating you to secure them.

As such, dopamine is a wonderful thing — it causes you to feel dissatisfaction with the status quo, to reach beyond what you have now to grasp for more, to explore, climb, and discover. It lends life a charge. It puts the thrill in the thrill of pursuit.

But, dopamine doesn’t last forever.

The novel becomes familiar. The uncertain becomes certain. The unknown becomes known. The future becomes the present. Endless possibilities become finite actualities. Your rose-colored fantasies become clear-eyed, concrete, complicated realities.

It turns out you and a recently-made friend don’t have everything in common after all. You’re not feeling quite as giddy about your girlfriend as you once did, and you’ve started having more disagreements. You generally think about these now not-so-new people in your life less often. You’re slower to respond to their texts, and when you do, you use fewer exclamation marks. Waking up early or moving a couch begin to feel like burdens again.

Your vacation is fun, but not everything goes the way you imagined it would. The new car you bought felt cool for a couple weeks, but now just feels like a car. A few months into your job, work becomes a mere matter of routine.

Working on your side project feels more like drudgery than fun. You decide that the new online program or organizational app you’ve been trying out wasn’t the right fit for you.

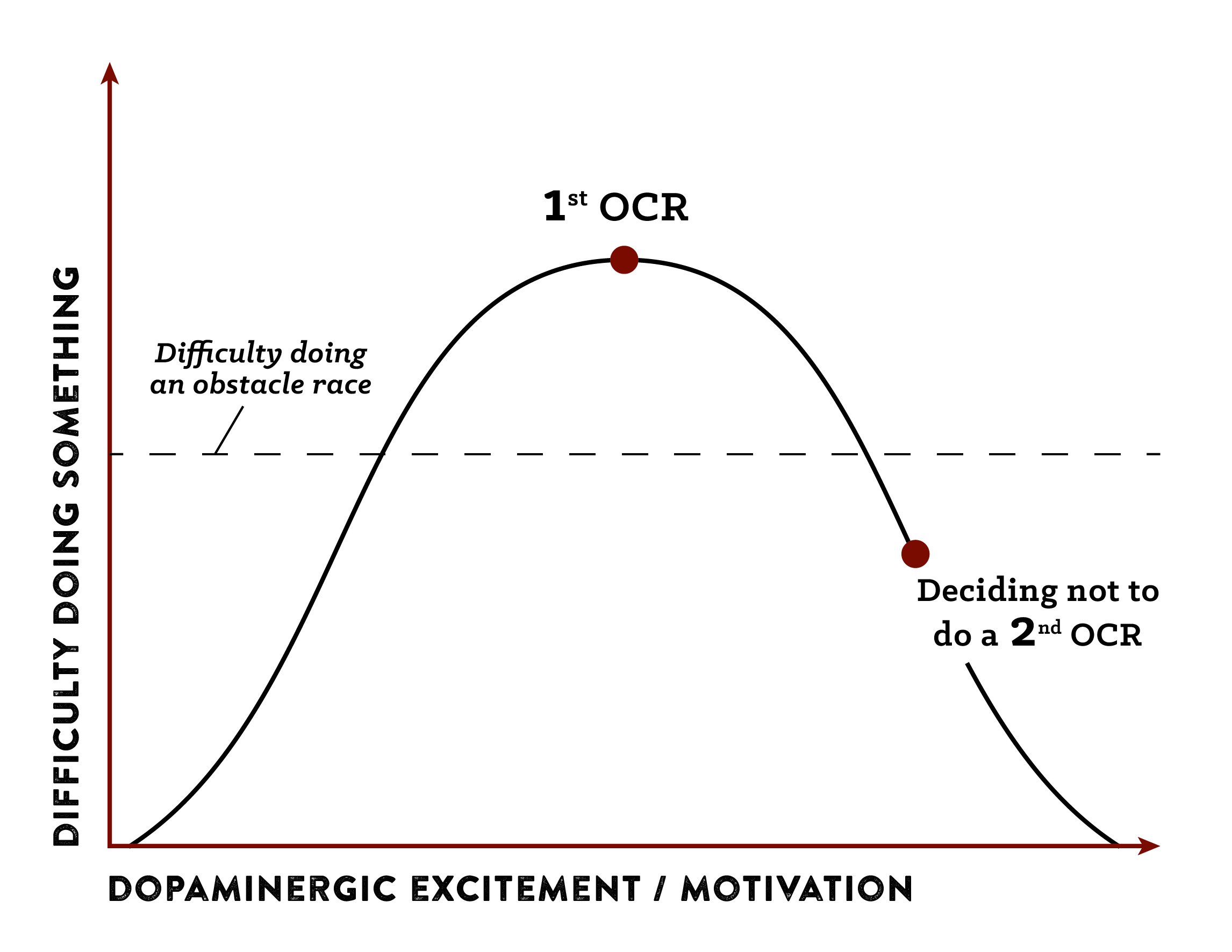

When dopaminergic excitement is higher than the perceived and real effort of doing something, you have the motivation to do it and it doesn’t seem as hard. For example, the first time you think about doing an obstacle race, the novelty, uncertainty (“What will it be like?”), and anticipation of reward (the satisfaction of crossing the finish line/posting a pic of you there on social media) creates a motivation greater than the perceived difficulty. After you’ve done the race, however, dopamine evaporates. When thinking about doing the race again, your excitement may be lower than the assessment of the effort it will take; consequently, you do not sign up again. The individual dopamine cycle then has culture-wide effects; when OCRs first came on the scene several years ago, they were wildly popular, as the novelty of the concept got people to try it in droves. Now they’re in decline, because the dopamine surrounding them is in decline.

Dopamine extinguishes itself whenever it gets in fact, whatever it’s been longing for in the abstract. When dopamine collides with reality, its chemical charge dissipates. The honeymoon period, which accompanies any new relationship or experience, comes to an end.

This can feel like a real letdown. It’s why when you finally achieve a goal you’ve been working towards, the moment can actually feel pretty anticlimactic. The lead-up felt more electric than the pinnacle!

In the midst of this letdown, you reach a crossroads. You have several options as to what to do next.

To avoid feeling let down in the future, you can stop hoping for things, stop going after things, stop having high expectations. But, as we’ll soon discuss, while getting stuck endlessly chasing after dopamine highs can be a problem, an equal problem is not having enough dopamine-induced charge in your life. Most of us need more of the electricity of anticipation, not less.

A second option is to move on from your current, dopamine-depleted pursuit to a new one, which will bring the neurotransmitter surging back. This can be fine if you’ve completed a “one-and-done” sort of goal: you took a trip, and although it wasn’t as perfect as you anticipated, it was still fun, and now you’re starting to plan your next vacation; you ran your first marathon, the satisfaction you felt has faded, and now you’re looking for another race to sign up for; you won a prize for a painting you passionately brought to life, and that was sure nice, but now you’re caught up in creating a new work.

However, dopamine doesn’t always extinguish when the anticipation of achieving a goal meets the reality of completion, but when it collides with an idealized conception of what it will take to reach that end. Sometimes dopamine dies out in an endeavor at a point in which you still have months, years, and even decades of effort left to put into it; if you want it to last, it will take ongoing, even never-ending, maintenance. You find yourself in a longer-term project where the work to be done lasts far longer than the dopamine-driven motivation to do it.

Dopamine can dissipate two years into a new relationship or a couple months into a new job; at that point, you can either start over and continue an endless, restless, and ultimately dissatisfying cycle of constantly chasing another dopaminergic ride — rabidly pursuing, then becoming bored with, then abandoning new friends, lovers, and enterprises — or, you can find a way to continue to sustain and build your interest in the people and work to which you’ve already committed.

The latter choice represents the third option available once dopamine has run its course, and it involves transitioning to a different source of satisfaction.

Shifting to the Pleasures of the Here and Now

Every part of living is divided in this way: we have one way of dealing with what we want, and another way of dealing with what we have. –The Molecule of More

Once the excitement of dopaminergic arousal dies out, and the initial thrill of something is gone, people think about calling it quits. In the absence of dopamine-driven motivation, they perceive the effort it takes to continue as more effortful. They think things should be easier than they are. Instead of only seeing the good, they start noticing the problems, the cracks. They wonder if someone/something is really right for them after all.

They may not be. But this judgment shouldn’t be tied entirely to your feelings of intrinsic enthusiasm and motivation. If you still feel like you have a good thing going, but just feel a little less giddy about it than you used to, it may simply be time to switch to a different source of pleasure.

As Daniel Lieberman and Michael Long explain in The Molecule of More:

To enjoy the things we have, as opposed to the things that are only possible, our brains must transition from future-oriented dopamine to present-oriented chemicals, a collection of neurotransmitters we call Here and Now molecules, or the H&Ns. Most people have heard of H&Ns. They include serotonin, oxytocin, endorphins (your brain’s version of morphine), and a class of chemicals called endocannabinoids (your brain’s version of marijuana). As opposed to the pleasure of anticipation via dopamine, these chemicals give us pleasure from sensation and emotion.

Lieberman and Long sum up this shift as making the “transition from excitement to enjoyment.” It might also be described as moving from choosing and pursuing to maintaining and building — a pivot we argue represents a major crux of adulthood.

To avoid the letdown that ironically comes with getting what you want, H&Ns need to take over where dopamine leaves off.

A good example for understanding how this works can be found in thinking about sex. When you’re seducing a stranger to sleep with you, dopamine comes on strong; the anticipation is highly charged. But as you orgasm, dopamine rapidly dissipates. With its departure, you can feel emptiness, a little disappointment, and even a bit of disgust for the partner who seemed so desirable just minutes ago; you want to get out of there and move on. To get another rush of pleasure, you’ll have to repeat the cycle of seduction.

When you have sex with a partner you’re in love with, on the other hand, the dissipation of dopamine post-coitus is compensated for by the Here & Now chemicals — the serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphins — that fill the void. You continue to take pleasure in the laughter and cuddling you engage in that evening, and in the conversation you have over breakfast the next morning.

With the random hook-up, once the dopamine died there was nothing but a void (this can also explain why people sometimes feel empty after masturbating). With the intimate sex, the pleasures of dopamine smoothly segued into the pleasures of the H&Ns.

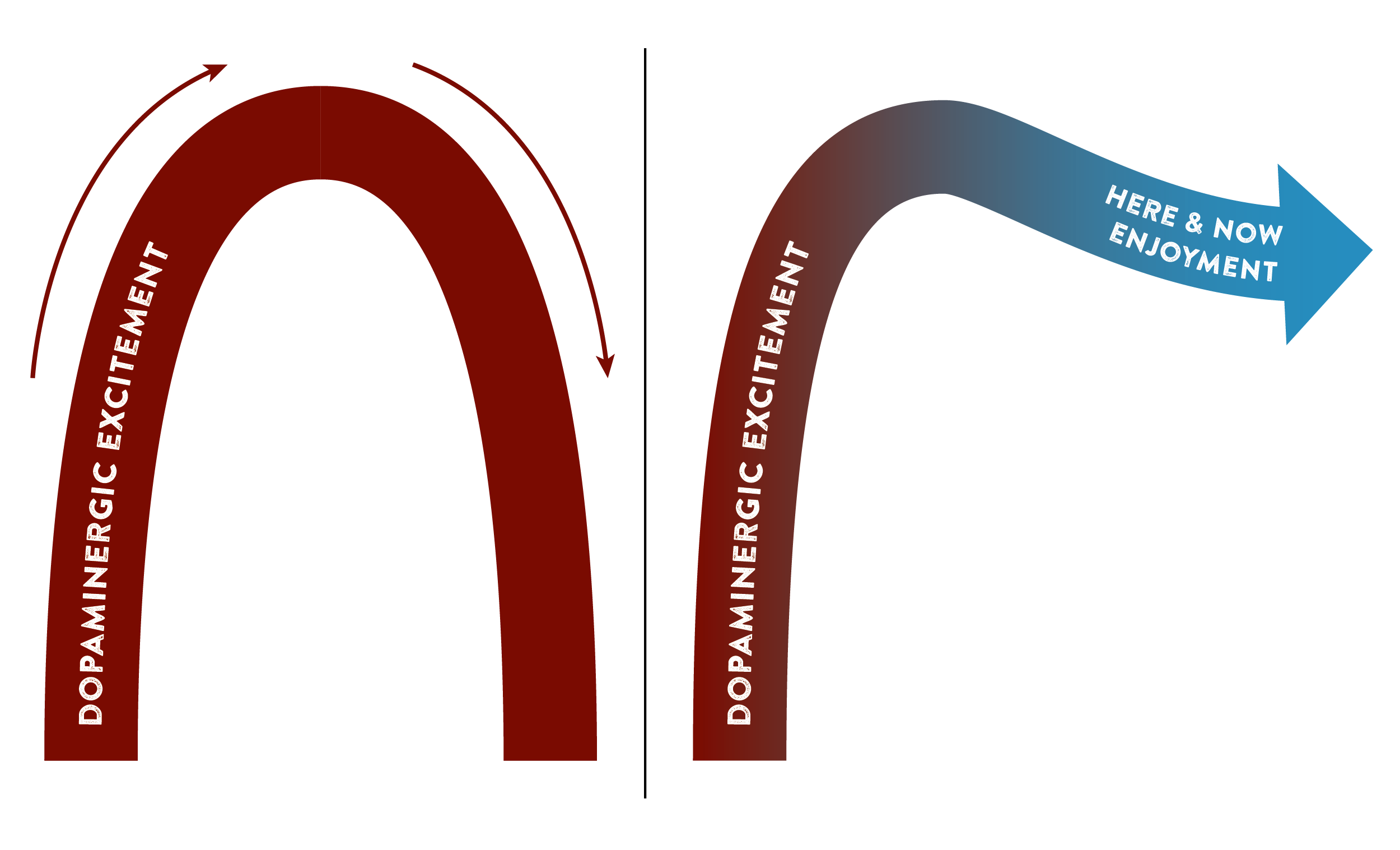

At left, the dopamine cycle alone; what Mr. Fleming called “the conventional parabola.” At right, allowing the satisfactions of the H&Ns to take over where dopamine leaves off.

Lieberman and Long write that the Here and Now molecules “allow you to experience what’s in front of you,” but require a “different set of skills” to engage. While the prompts of dopamine operate in a more involuntary way, tapping into the H&N chemicals takes more intention.

As they constitute the chemicals of the here and now, experiencing them naturally involves learning to be completely present — living mindfully in the moment. You drink up what’s happening with all your senses — you seek to touch, taste, hear, and see the people you’re with, the environment you’re in, and the activity you’re engaging, to the fullest extent possible. You take the time to reflect on the warmth of looking into another person’s eyes, of laughing in a group, of sinking your teeth into a juicy burger. You really take the time to appreciate and enjoy what you have.

You also have to be deliberate about creating the contexts in which H&Ns flourish. While dopaminergic arousal ensures that you practically can’t help but think about and reach out to people, or work on a task, once that dies down, you’ve got to be more proactive: “I haven’t checked in with so-and-so in a while — I’ll text him to see if he’s available for lunch”; “I don’t feel like working on this task, but I really want to keep excelling in this field, so I’ll just be a professional and get going on it”; “Doing date night with my spouse isn’t convenient this week, but we’re going to go out anyway.”

The catch-22 about transitioning from dopamine to H&Ns, is that to experience the pleasures of the Here & Now, you’ve got to make good times happen in the here and now, but making good times happen is harder in the absence of dopamine; once it dies, it’s thus very easy just to let things drop and drift. To get out of that cycle, you have to be intentional about continuing to do the things you used to do in the presence of dopamine, in its absence.

There’s a bit of a red pill quality to understanding how dopamine operates in your life; once you do, it’s hard not to readily identify when it’s playing a role, so that instead of being unabashedly giddy and hopeful — “This is the thing that’s going to change my life!” — you can get a little demoralized and cynical: “No, I know what’s going on here — dopamine’s just inflaming my brain. This isn’t going to last.”

But it’s empowering too; now when you encounter friction in some pursuit, you won’t automatically abandon ship, only to repeat the exact same cycle again (“This time is different. This is the thing that will change my life!”). Instead, you’ll know, “I’m not necessarily on the wrong track, I just need to switch to a different source of satisfaction.”

Why Long-Distance Relationships Generally Don’t Last

Once you understand the interplay between dopamine and the H&Ns, you can better understand why long-distance relationships usually don’t work out.

At first, the novelty, tension, and uncertainty of a long-distance relationship keeps its two participants longing for each other and motivated to obsessively text, call, and Skype. But as the newness melts away, and the idealized vision of what it would be like to continue a relationship while apart, collides with the realities of how difficult doing so can be, dopamine begins to dissipate.

But, because the lovers are in two different locations, there are no Here & Now chemicals to take its place. Thus when dopamine dies, the relationship dies with it.

Seeking Harmony Between Dopamine and the Here and Now’s

Dopamine is a place to begin, not to finish. –The Molecule of More

Life isn’t about operating on either dopamine or H&Ns but rather seeking a balance between both.

If you’re too dopaminergic, you’ll end up restless, perennially dissatisfied, and unable to build and maintain anything of depth and lasting significance. You’ll just keep trading one goal or relationship for the next, and abandon one half-finished project after another.

But if you’re too content with the H&Ns, you can become complacent — overly satisfied with what you already have to the point of stagnation.

The key is to toggle between these two sets of chemicals, as appropriate — allowing yourself to be satisfied, but never wholly so; content, and yet eager for continuous growth. You have to be able to enjoy the excitement of the conquest, and be able to hold onto what you secure.

As Lieberman and Long point out, not only are these two modes of operation not at loggerheads, they work together. The information you gather from being present in the here and now, can lead you into the pursuit of a new, dopamine-driven idea or relationship.

At the same time, even when dopamine stops being the primary driver in some area, that doesn’t mean it has to disappear entirely. Even when the pleasures of a job or relationship have become mainly of the H&N variety, it’s still possible to bring the butterflies back from time to time. Taking a new avenue within your career, or doing new things with your old spouse, can reactivate the charge of dopamine again. Even when you’re on a steady, familiar path, there are still ways to take little turns of novelty along the way.

Dopamine and the Here & Now’s; the thrill of the hunt, and the enjoyment of the quarry; you need both to unlock your potential and achieve real happiness.

0 Comments